SUNDAY PROFILE: Nan Nicholson, activist and author

Liina Flynn

15 February 2020, 8:27 PM

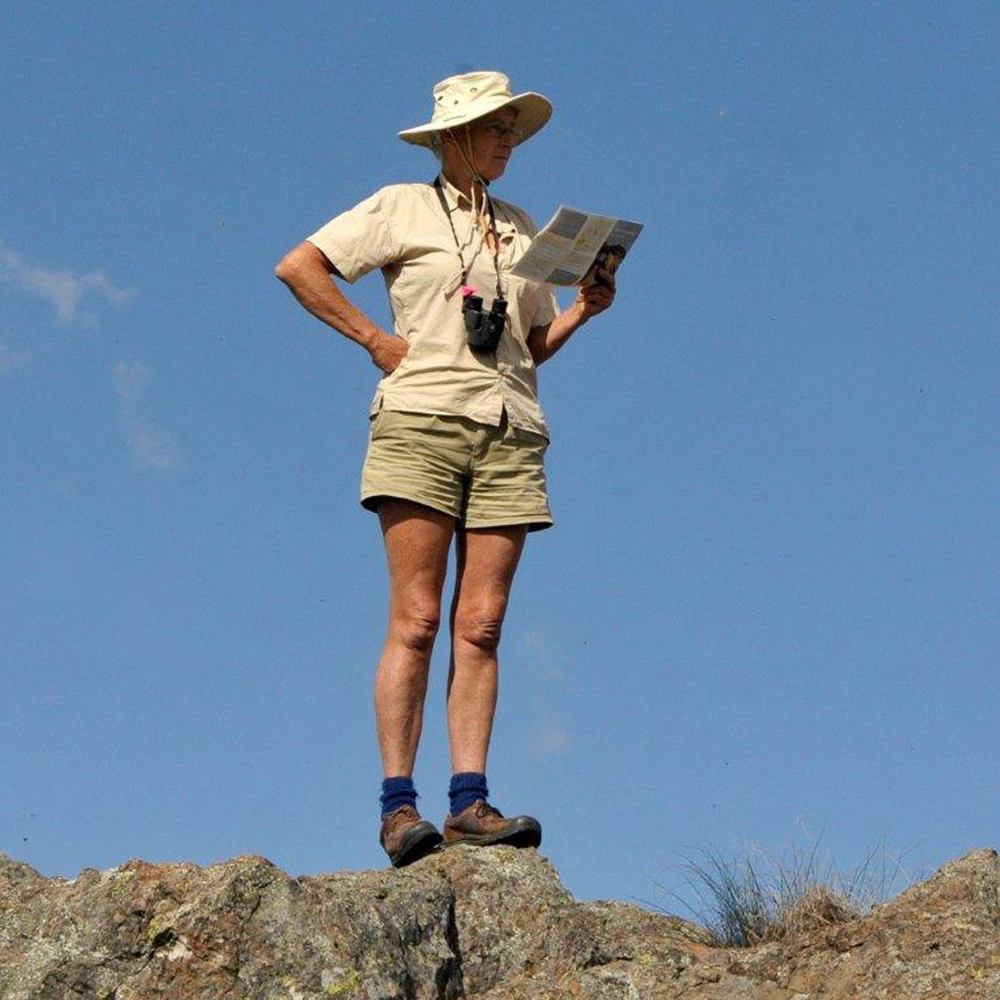

Nan Nicholson.

Nan Nicholson.While she’s living a quieter life these days, the activist in Nan Nicholson will always shine. From the early days of surviving in the rainforest of Terania Creek and being instrumental in saving the area from logging – to propagating rainforest trees and writing books - Nan’s care and compassion for the forests and the land is always her driving force.

The recent bushfires came close to destroying her home in Terania Creek and fuelled the activist in her. Now, she renews the call to action to stop logging what is left of our Australian forests and address the changing climatic conditions.

After 40 years of living in the rainforest at Terania Creek, Nan Nicholson and her partner Hugh now live in the Channon and run the Channon Village Camping Ground.

Nan said she was ready for change after living on “terrible dirt roads” for years in a damp, tropical forest climate.

“The kooris laugh at us for living in rainforest,” Nan said. “They used to visit, but not live there - Aunty June says to me that it’s a burial site at Terania Creek and she won’t go there.

Nan and Hugh at Terania Creek after the bushfires.

“It was great when we moved here six years ago because it was a lot easier for us to go to the Bentley gas blockade. It’s an easier, more accessible place to live and we can grow more food.

“We don’t regret coming here, but we do miss the wild. We are regenerating the creek here and planting trees for the koalas and they are moving in.”

According to Nan, the camping ground has “primitive, cold water for people who like it simple”, and she encourages women travelling on their own to stay there in a safe place.

“It’s not for party crowds and there’s a limit of seven days to stay - or people will want to move in permanently,” she said.

“We live on what we grow and eat chooks and eggs. The camping ground helps us make ends meet – selling books is a tough way to make money.”

Over the years she and Hugh lived in the rainforest, they collected and propagated rainforest seeds and grew them in their own nursery.

Then they wrote books about rainforest plants, which they sell online on their website https://rainforestpublishing.com.au/

“We used our experience to produce a resource of six books detailing how to grow and identify them,” she said.

“It’s priceless information that was going to vanish and we knew it was information everyone needed to have.”

Nan and High after the recent bushfires with their favourite brushbox tree.

Fires

Nan Nicholson remembers well when the bushfires in Terania Creek area started last year on November 8.

It was a fire that was burning in some of the wettest rainforest in Australia - it was something she had never seen happen before.

After a long drought, the rainforest was now tinder dry and succumbed to a slow creeping fire that became part of the 80,000 hectares of forests that burned on the North Coast of NSW last year.

“It broke my heart – it was a big time for all of us and we are still coping with grief,” Nan said.

“The forest blew up like a volcano and Hugh and I sat on a hill and watched the valley burning. Our house nearly went too, but we were there to fight it, with four fire brigades to help us.

“It taught me a lesson that if it’s dry, it will burn - and we really learned that.

The Terania basin.

“The sclerophyll forest is coming back now - some trees will only come back from seeds. From the air, the canopy looks intact, but the palms are dead – their fronds are dry and flammable and the base is dry, cooked and shrinking.

“With time, we’ll see what will regenerate – it will be interesting to see what sprouts, but if we have another dry season next year and get more fire, the forest will cop it again.

“We need to work out now how to manage the weeds as they come up – what protocols do we use?

“Some of the areas at the bottom of the valley with the very wettest soils are relatively ok, but not unscathed.

“The fire mapping doesn’t show the understory where fire had trickled through under the canopy and boiled the base of palms overheating them.

“The trickle burn of fire had moved through the leaf litter until it surrounded big trees and created a chimney of fire in the trunks.

“Forestry did some radiocarbon dating on the old brushboxes and the last time bushfire was there was 1000 years ago – who knows what condition we were in them when it was so dry.

“This could happen again next year – where it’s so hot that things ignite – if we are on that path, we are in deep trouble.”

The Terania basin on fire.

Terania Creek history

Nan and Hugh first came to Terania Creek in 1974 as “refugees wanting to live in the bush and be self-sufficient”.

“So, we bought a derelict farm just after the Nimbin Festival – it was 106 hectares at the top end of Terania Creek against the state forest,” she said.

“Then we went back to Canberra to our cattle station jobs to pay for it. We didn’t realise at first that the property would disappear into weeds in this subtropical area.

“So, we came back with nothing, set up a tent and worked out how to survive.

“Within months, we were shocked when we realised the forest was going to be clearfell logged - it was so beautiful and we expected it to stay there.

“That’s when we realised there had also been movement of people into Terania Creek who wanted to get back to the land and grow in the fertile volcanic soil.

“Within months, we were thrust into a forest campaign, when all we wanted to do was put our heads down and survive.”

And so, began a battle to save the rainforest at Terania Creek, which saw blockades, protests and campaigning continue until 1984, when the area was finally protected and turned into the Nightcap National Park.

“Then we spent the next few decades living at Terania Creek, bringing up two kids and making a living with a rainforest nursery and wrote books about rainforest plants,” Nan said. “We learned a lot very quickly.

“I don’t regret our involvement in rainforest preservation. I always felt this was my country.

“As a child I visited the Border Rangers National Park– and I knew I needed to come back there.”

Nan reading a map.

Fight for the forests

Nan said she fell in love with the large Brushbox trees in the forest and that they would become integral to the fight to save the forests from logging.

“Whether the trees were sclerophyll or rainforest types was the argument that Forestry gave – if it was sclerophyll, they wanted to say it could be logged,” Nan said.

“We said it doesn’t matter - it’s old growth. When that term first arrived, I realised that was the term we needed. Old growth is big old trees with hollows that need to be protected.

“A lot of battle for forests after Terania Creek went along the lines of looking after rainforest, them old trees, then native forests in general.

“Now, it’s time to stop all logging of native forests, especially after all the fires.

“I thought after the fires, it would be obvious we needed a break, but the logging industry is saying we need to log just as much. It’s never ending – we can’t give up.

Campaign strategies

The successful campaign to save Terania Creek has often been heralded as the strategy blueprint used by environmentalists for future actions across Australia.

“When we fought to save Terania Creek, it was many years of letter writing and petitions and talking to government bureaucrats,” Nan said. “It was only four weeks of blockade

“It’s the same model we used in the fight to stop the gasfields. It was years of work - and one blockade that made people pay attention.

“We are not the first people to fight hard to save the environment - it was the kooris who did it first. We might have been the first Europeans to blockade to the protect forest, but there’s been many techniques developed since then.

Nan locked on to a bulldozer at Braemar State Forest.

“I love how on blockades, skills come from nowhere. People spot a gap and leap in and do something ingenious.

“We didn’t need lock-ons in the early days - you didn’t need to dig up roads to make it impossible for police paddy wagons to get to it.

“We didn’t need to because there were no trespass laws and we could ‘black wallaby’ and swarm everywhere in the forest to stop the logging.

“Now, they’ve brought in legislation and big fines. It shows me how effective we are – it’s dismaying but confidence boosting.

“Early on, we knew that non-violent direct action was the way to go. We would have been stupid to go down the violence road - violence equals tissue damage.

Nan and her grandson.

The future

Since 1984 and the NSW government’s declaration of the Nightcap National Park, Nan said she’s realised how quickly political will can change, putting any forests left in jeopardy of being logged to fulfil logging quotas.

“It’s not safe now and after fighting for so long to get a national park, it’s horrible to think that it might vanish,” she said.

"We need to face reality and encourage more young people to come out now and help save what we have left.”

BLOGS