SUNDAY PROFILE: Losing a hand won't stop Nathan Parker flying

Liina Flynn

28 November 2020, 6:46 PM

With one robotic arm, 25 year old Nathan Parker is now a flying instructor at the Northern Rivers Aero Club (NRAC).

But achieving his dream of flying planes has come only after his persistence, strength and resilience saw him emerge from a major setback.

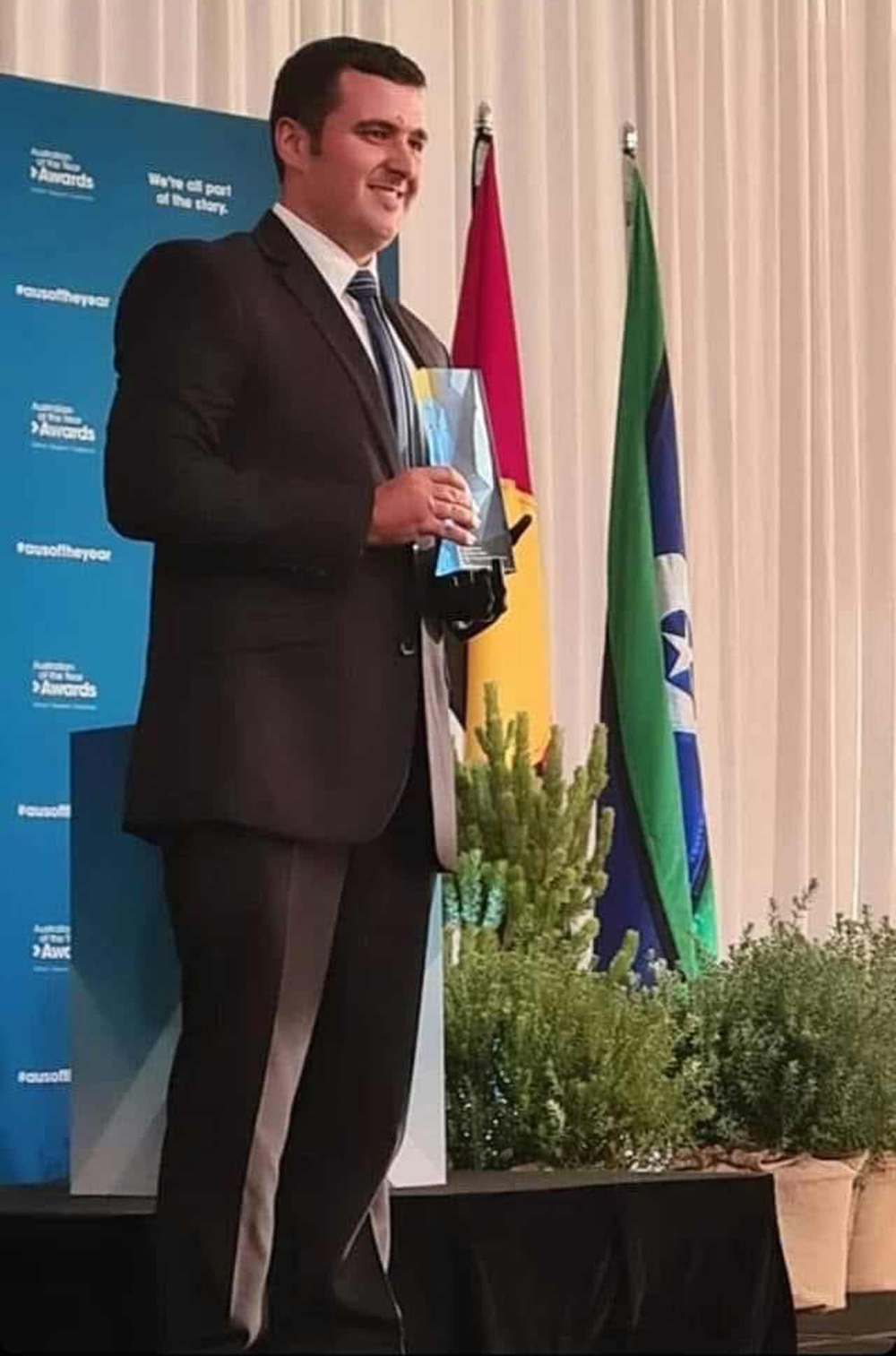

In fact, the Goonellabah resident has just been named NSW Young Australian of the Year at an awards ceremony in Sydney recently.

Nathan tells the Lismore App his story:

“Ever since I was six years old my sole goal was to become a fighter pilot in the Airforce," he said.

“My grandfather served for 45 years in the Royal Australian Navy and I learned about what he’d done in the military and it helped keep the fire burning.

“In my childhood, I did watch Top Gun and went to airshows and it fed the passion. I never wavered from my goal and was always working toward it.

“I joined the Airforce at 18 years old and in 2014, I went to Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra and did my university degree and military officer training at the same time.

“At the end of my second year was when the bus accident happened.

The accident

“As part of degree and officer training, our university break became the time for us to conduct the military training we had to do. We were headed to Jervis Bay for a week of activities, learning to become better leaders and testing ourselves.

“We finished that and were headed back to Canberra when the bus went round a bend on a quiet country road and rolled onto its left hand side.

“My hand became pinned between the bus and the road and it was 45 minutes before the ambulance arrived and two hours before they were able to get me out of the bus and onto a helicopter to go to hospital in Sydney.

“They think when the bus rolled over the glass shattered, my hand fell out and was pinned under the bus as it slid sideways down the road.

Glass shattering

“I have a full memory of the bus rolling over, I have the audio of the glass shattering and the bags falling and people screaming. I was lucky to be awake through it all and to have awesome guys climb in an save my life and apply torniquetes to my arms and make sure I was able to bet out of the bus.

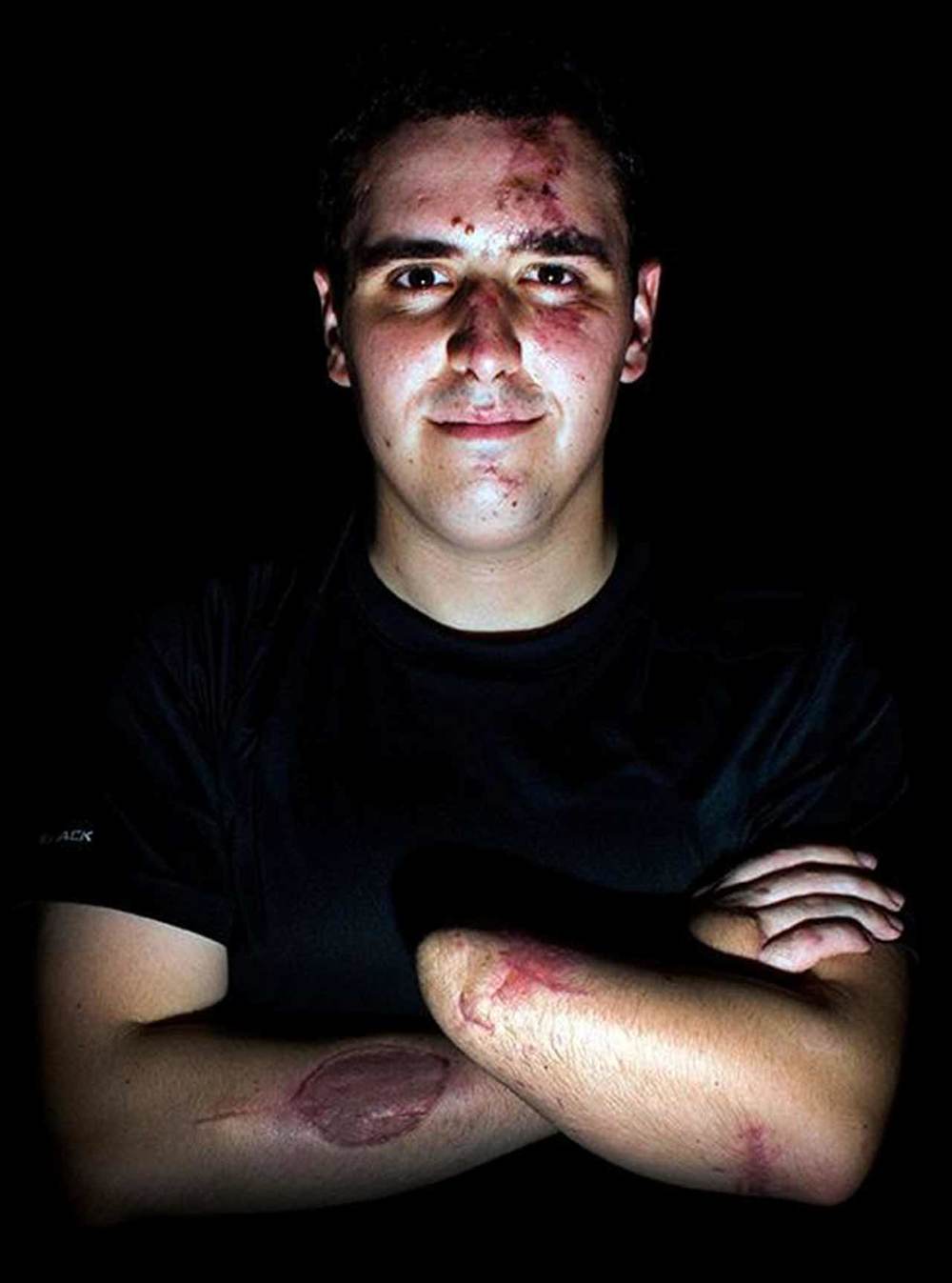

"There were about 50 people on the bus and about 27 were hospitalised for stitches or skin grafts. Three of us were airlifted in serious or critical conditions.

Hospital

“In hospital, before they took me into that first surgery, the doctors asked me if they could amputate my left hand. They didn’t know what the extent of the damage was then. I didn’t hesitate to say yes – it was about doing what had to be done to keep me alive.

“I woke up without my left hand and suffered tendon damage in my right hand which was stitched back together. I also had multiple face lacerations and glass in my face.

Rehabilitation

“I was in hospital for two weeks and the ongoing rehab was about seven months before I went back to training at the academy.

“I had to learning to do basic things again like get dressed, feed myself for two months after the accident. I didn’t have the prosthesis for a while so we could let the stump heal and then I learned to do things single handedly.

Prosthesis

“Because I was in the military, I was lucky to be fitted out with an advanced prosthetic robotic hand.

“It speeded up my rehab, but I had to learn the most basic tasks like learning how to pick up a peg from a peg board. At first, I was doing six to eight hours a day of training and rehabilitation to learn to use the hand.

“It has two sensors – electrodes - inside the socket of the prothesis and they press against the forearm of my residual limb. When I flex the muscles, it picks up the signal and translates that to open or close or rotate the wrist.

“Because I didn’t have a hand with a wrist it was about trying to build up flexion muscle strength to be able to use the prosthesis all day.

Graduation

“The military did a lot to look after me and give me the resources I needed to get me back on my feet.

“I was good at rehabilitating from my injuries and the force let me go back and continue my degree and training and look at other options in the military.

“So, I resumed my studies in the Bachelor of Technology Aviation.

“I was lucky enough to graduate the military side of the training alongside my peers – the same cohort I joined the ADF with and had the bus accident with. I finished my degree the following year.

“If all went to plan, I would have progressed onto learning to be a pilot, but unfortunately my injuries made it impossible for me to continue done that pathway.

Pilot dreams

“The military came to me and said we want to see what you can still do.

“In 2017 they looked at me to see if I could still progress onto the pilot’s course and unfortunately, due to the nature of military flying, the risk, and my injuries, it wasn’t likely I would be able to

progress down that military pathway.

“I didn’t have the same sense of touch and military aircraft are complex and require fine motor skills – that was one of my barriers they identified.

“I knew I still wanted to fly and wanted to see if I could still do that - so I took time away from the military.

Shattering

“For me it was pretty shattering. Losing that dream of flying military planes was far more devastating than losing the hand.

“It was a challenging time in 2017. But I was lucky enough to have support to refocus on other opportunities.

Northern Rivers Aero Club

“Three months after the accident in 2015, I was back home in Lismore doing some rehabilitation and I set a goal to get back in the air.

“I went to the Northern Rivers Aero Club – where I’d learned to fly as a 15 year old going through school. I went to see what I could still do and the members there were so supportive.

“For them there was never really any barriers. They said we will put you in an airplane and see what you can do. I was lucky and spend time working on the challenges of getting my recreational

flying licence.

Recreational flying

“So, when the military decided I couldn’t fly in the military capacity, I still knew I had options to fly recreationally and wondered if I could pursue it as a career.

“So, then I started some pretty intensive training at the NRAC to see what my limitations were with the prosthesis.

“Now I have worked through the private pilot and the commercial pilot level of training and can now be employed to fly in a commercial capacity in civilian flying.

Teaching flying

“Now, I’m incredibly lucky to be able to teach people to fly recreational aircraft.

“Even though it’s not the military jets I imagined I’d be flying, I’m enjoying it just as much being able to share my passion for flying and pass that on and help others realise the same goals and ambitions I once had.

“These days it’s getting more affordable to fly - there’s a scholarship program people can apply to if it’s something they really want to do.

“I’ve been lucky enough to train seven or eight people to the stage where they can now fly locally.”

Motivational speaking

“I’m really enjoying doing motivational speaking to pass on some of the lessons I have learned through the challenges I’ve had to overcome.

“One of the major lessons I’ve learned is the idea of resilience.

Resilience

“Resilience is nothing but a series of consistent small choices by you one at a time and no matter what goes wrong, there’s always a choice that can be made.

“For me, when I was trapped in the bus, it was about breathing and getting to hospital with a pulse. Then in hospital it was about what’s the next small choice I can make to keep moving forward to keep getting better. It’s about keeping moving forward in whatever way you can.

Where did the resilience come from?

“I think the military training had an impact – as well as the support of family friends and team mates.

“I’d always thought about motivational speaking after the days in hospital.

“I was lucky enough to be visited by a navy clearance diver who lost an arm and a leg in a shark attack - he gave me a number of key lessons to get through those initial times.

“I decided that wasn’t going to be the end of my story – so going forward, what could I do to help one person work through the darkest days?

“I went through some tough, dark times and if I can help someone obtain those lessons without having to go through the school of hard knocks, it will make the accident worthwhile.

Schools

“I’ve been speaking to young people at schools who are going through some big challenges, especially during this last year with Covid-19. I’ve also spoken to charities and community groups.

“It’s a real privilege and ideally, I’d like to be able to talk on a national level and share a message of resilience and hope for people.

Inspire people

“This year It’s been about getting my flying goals ticked off and as restrictions ease, I look forward to doing more speaking and share my message and inspire more people.

“One of the biggest things I’ve learned is that we have far greater capacity than we think. day to day, each and everyone of us has the capacity to over come the challenges put in front of us. Now more than ever, the other key message is don’t be afraid to seek help.

“For me, I’d gone from being a fit and healthy 20 year old, aspiring to fly technologically advanced airplane - to needing help to feed myself.

“I learned its never a bad thing to ask for help. It actually makes things easier. There’s not shame in that – it’s actually courageous to seek out assistance.”

Invictus Games

Nathan became involved in the Invictus games in 2017 as he rehabilitated from his injuries. He won nine medals, including three gold medals. He has also won 17 medals from two US Warrior Games.

“The Invictus Games is a Para-Olympic style sporting competition founded by Prince Harry in 2014 in London,” he said.

“Its purpose is to rehabilitate wounded servicemen and women. I got involved in 2017 after the accident.

“I had the opportunity to compete in sports on the world stage, but the biggest benefits were gaining community and seeing different people and hearing about their stories and journeys overcoming injuries and refusing to give up.

“I found the people I met were ringing me to check in when they knew I would be going through tough times.

Sports

“My main sports in the games were indoor rowing, and sprinting. but I also participated in swimming and volleyball as well.

"It allowed me to redefine my limitations and try sports I thought I’d never do before the accident, let alone with my new injuries. It was amazing to see how other people adapted to also play sports.

Community work

“I’ve been helping out with a number of local organisations Amp Camp three day camp for 12 to 18 year olds who have amputations. Some of them had never seen another amputee before and we bring them together and get them to do activities and pass on lessons.

“I also work with The Hangar Mentoring – we use aviation to mentor youth through challenges. For me that’s the perfect mix of two passions.

“Some of the young people might be disengaged or struggling and we teach them techniques how to change your perspective, take responsibility in changing your own situation.

“It’s about giving them tips and tricks to take back to their normal lives and also learn to fly.

NSW Young Australian of the Year

Last week, Nathan was named NSW Young Australian of the Year at an awards ceremony in Sydney.

Nathan said the NSW awards were about recognising people who are achieving and working to make a difference in their communities.

“I hope winning the award will allow me to keep doing the work I’ve been doing, working with young people and as a motivational speaker,” he said.

“My passion to inspire others to turn the toughest times into greater opportunities and not let setbacks stop them pursuing what they want to achieve in life.”

“I feel privileged to have been one of the 16 finalists over the four awards categories.

“Now, I will progress through to the national awards Australian of the Year awards on January 25, 2021.

“I could still win next year, I don’t know what will happen.

“I just love the idea of meeting other people and learning about what they are all doing in their communities.”

Contact

To find out more about Nathan, visit his website https://nathanparker.com.au