SUNDAY PROFILE: Lismore lapidary club turns rough diamonds into gems

Liina Flynn

11 December 2020, 1:52 AM

Lismore Gem and Lapidary Club secretary Bruce Copper holding a large zircon stone found by his fossicking father-in-law.

Lismore Gem and Lapidary Club secretary Bruce Copper holding a large zircon stone found by his fossicking father-in-law.Inside a pavilion at the Lismore Showground, there’s a hum of electric motors, drills, saws and happy voices. Members of the Lismore Gem and Lapidary Club are creating works of wearable art out of stones and metal.

The club's appropriately-named treasurer Bruce Copper greets me and tells me club members have their noses to the grindstone at the moment preparing to host next year’s Gemfest at the Showground in May.

It's the biggest annual show in Australia that's devoted to lapidary and craft, and while it was cancelled this year due to Covid, Bruce said it looks like next year will go ahead, but with modifications.”

Lapidary

The word lapidary comes from the Latin 'lapis', meaning stone, and the art of lapidary involves turning rough stones into attractive ornaments for wear or display. All around, club members are cutting, grinding or polish-ing rocks on different machines; turning what look like lumps of stone into sparkling gemstones or smooth, colourful crystals.

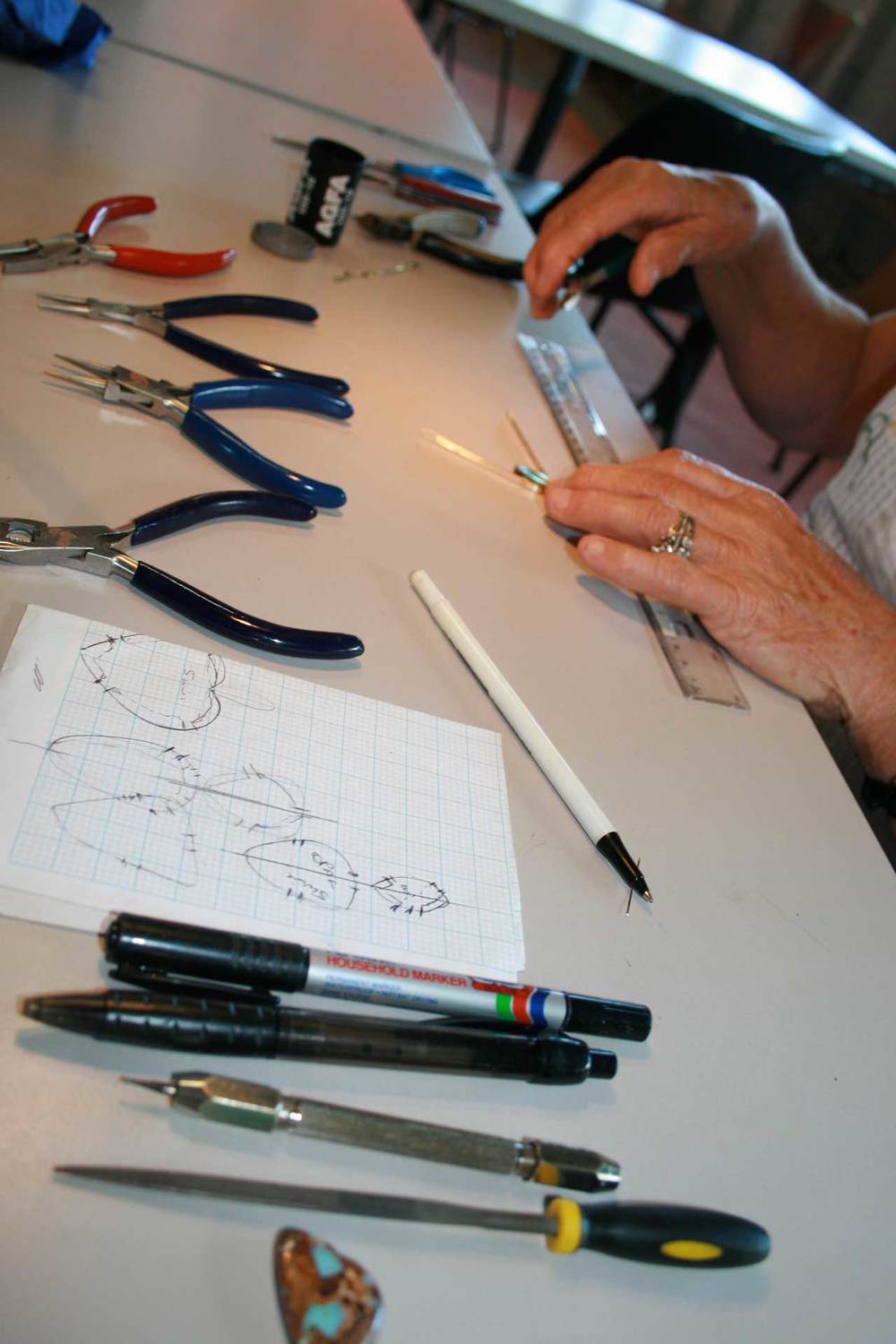

Bruce's wife Chris is sitting at a long table nearby with pliers, silver wire and sparkling stones laid out before her. She's making a necklace with a double chain of silver links and orange carnelian stones.

She creates each of the links by winding silver wire around a long metal rod called a mandrel, then cuts each link out of the spiral with a small hand saw to ensure the edges are smooth and fit together well.

While most of the jewellery you'll find in jewellery shops is laser welded by machines or is made from cast-ings, Chris said that the jewellery made by club members is mostly created by hand, although the club does make rings and 'findings' (the settings stones are mounted in) out of castings made by pouring melted silver into plaster moulds.

"It's lots of work to clean them up, but it's quicker than fabricating a ring," Chris said.

Chris has been making jewellery for over 30 years and joined the Lismore club with her husband 20 years ago. They brought with them their knowledge of lapidary skills and enjoy sharing it with other club members, teaching them new ways to make things.

"I used to work in a jewellery factory and have always loved jewellery," Chris said. "My great, great grandfather was a jeweller."

Copper and Cann

Before Chris married Bruce and took the surname Copper, she was a Cann. Her mum was a Kitchen and her dad, William, was known as Billy Cann.

Chris took her relationship with metals seriously and followed her path toward making jewellery and these days, has progressed to using precious metals such as gold and silver to make her art. She has a chest of drawers filled with jewellery pieces she's made over the years and is always looking for things to make jewellery out of.

Chris used to enter jewellery competitions, where lapidary clubs compete to see who can make the finest piece. In competitions there are different judging categories for jewellery pieces including polish, difficulty and cutting.

"Polish is a big one," Chris said. "There is lots of work in silver, polishing the fire-scale off. Fire-scale is a greying of silver caused in the soldering process and once, I spent a whole week polishing the fire-scale off a necklace."

Sitting next to Chris is her brother, Peter Cann. Peter is deft at plaiting silver and copper wire into bracelets with Celtic knotwork-like patterns. With a pair of pliers in each hand, he's making a bracelet using two kinds of silver wire. When each wire is twisted, it gives different effects and a flatter wrap

"You need to have strong wrists to keep the weave even," Peter said.

Soldering and cabbing

Peter also learned to solder and make cabochons ‘cabbing’ (French for 'bald head').

Cabbing involves shaping and polishing gemstones, such as opals, into smooth, often irregular-shaped stones. Stones have different gradings, from soft to hard, and softer stones that could scratch easily are often shaped into cabochons to fit a particular setting or 'finding'.

"Working with harder stones such as jasper and agate is easier for a beginner, they won't chip as easily as softer rock such as obsidian, which is a volcanic glass," Peter said.

Another club member, Vicky Wallace, sits nearby wrapping a boulder opal (an opal that forms in a boulder) with silver wire.

Although she has arthritis, Vicky can use pliers to wrap stones into artistic wire creations and enjoys creating unique gifts of jewellery to give to friends. In front of her are numerous pairs of pliers, all a little different to each other; flat pliers, rounded pliers, skinny-nosed, curved-end and other specialist pliers.

"I have about 40 pairs, but you don't need lots," Vicky said, as she shaped silver wire around the outside of the opal.

"Getting the shape of the stone is the most difficult, but the most important thing. The first time I tried to do it, I broke the wires off before I finished it but that's okay because we can melt down the silver and reuse it."

“I'm pretty handy with a pair of pliers and a roll of copper wire, but I can see that when working with a precious metal like silver, it's best to try and get it right first time because it's not real cheap.”

Sterling silver

Sterling silver is an alloy of silver containing 92.5% by weight of silver and 7.5% by weight of other metals, usually copper. Some silver these days is made with germanium instead of copper, which gives the metal anti-tarnish properties.

Cutting rock

Bruce takes me to another area of the workshop and uses a special bench saw to cut a chunk of rock into slices, exposing the orange-coloured carnelian stone inside. He uses water on the saw to keep it cool while cutting the rock into shape. Nearby, others are using different grinding wheels to shape, sand and polish rocks and fossils.

These days Bruce doesn't cut too many stones but he enjoys passing on his knowledge to others. Before he retired, he bought a lot of the equipment he now has because he knew he wouldn't be able to afford to buy it all once he had retired.

Hobby

"It's a hobby, and it takes lots of time; I wouldn't want to try and make money out of it," Bruce said. "I enjoy the social element of the club; people are friendly."

Bruce studied geology and chemistry at university and has always been interested in fossicking. He travels around Australia to look for sapphires and other gemstones in the gravel of ancient riverbeds, where the gems wash into after the rock they formed in eroded away.

Fossicking

"Fossicking is hard work and you can look for years and find very little," Bruce said.

He holds up a zircon, a freeform shaped stone his father-in-law fossicker found in Harts Range and gave to him.

"This is a special stone for me," Bruce said. "I've found zircons before, but never one as big as this. My wife is going to set it. It's a 20-carat stone and would be worth about $900 if I'd bought it."

A carat is a measurement based on weight and five carats equals one gram. Some stones take a lot of work to turn them from looking like a lump of rock into a sparkling gemstone, especially when the rock is full of im-purities (inclusions), cracks or fractures that need to be cut out.

Carats

Sometimes, a cutter needs to buy 20 carats of stone to be able to cut a five-carat gem out of it.

Bruce said that many of the cheaper stones we can buy today, such as amethyst or quartz, are often cut over-seas by people being paid very low wages and we don't realise the true value of the amount of work that it takes to create them.

"Precious stones such as rubies, sapphires and emeralds are so expensive because they are so hard to find," Bruce said.

About 80 to 90 % of affordable stones you see in the jewellers shops today are produced synthetically; gem-stones are melted down and reformed without impurities.

A ring made with a one-carat fabricated emerald might cost about $600, but a natural emerald would cost thousands of dollars.

"I once bought a rough blue topaz for $20 at a show and cut out of it a 59-carat blue topaz. Normally, it would have cost me $300 to buy the material to cut it out of," Bruce said.

Faceting

Ian Rodgers is faceting a red garnet he started working on last week. He has been a fossicker for years and joined the club recently to learn to cut gemstones.

He switches on the faceting machine and, while it gently hums, a metal disc coated with a fine layer of diamond (called the lap) spins around.

With the tiny garnet glued to the end of a long metal 'dop stick', he puts some water on the lap to lubricate it and touches the garnet to the coarse disc before quickly removing it.

He checks the angle he has just ground onto the stone against a faceting guide that shows the exact angles needed for a garnet to reflect light.

When a gemstone is faceted, it involves cutting numerous planes of exact angles into the stone to maximise the reflective properties and minimise light loss

Synthetic stones can often be identified because they flash a lot of colour due to their high refractive index and high colour dispersion.

"When a gemstone is faceted, the underside, called the pavilion, is cut in an iceberg shape for a very scientific reason; to reflect light and give the right sparkling effect," Bruce said.

Colour, cut, clarity

"There are three important things in a stone: colour, cut and clarity. We know from years of experience about the physics of optics and refractive indexes and we have worked out the critical angles needed to allow light to reflect and not be lost through different types of gems.

"If a piece of rough is not deep enough and the stone is cut on a too shallow angle, it won't perform. It would be like a window stone and you could look through it and it wouldn't reflect. Also, if a stone is cloudy or has inclusions, not much light will reflect out of it."

Join

If you would like to join the Lismore Gem and Lapidary Club and learn the craft of jewellery making, the club meets at the Lismore Showground on Tuesdays from 2pm,

Thursdays from 9am and Saturdays from 9am.

For more information check out the website http://www.gemclublismore.org.au

Children are welcome to come along with their adults too.