SUNDAY PROFILE: Emma Stone gathers stories of Coopers Creek

Liina Flynn

12 September 2020, 8:41 PM

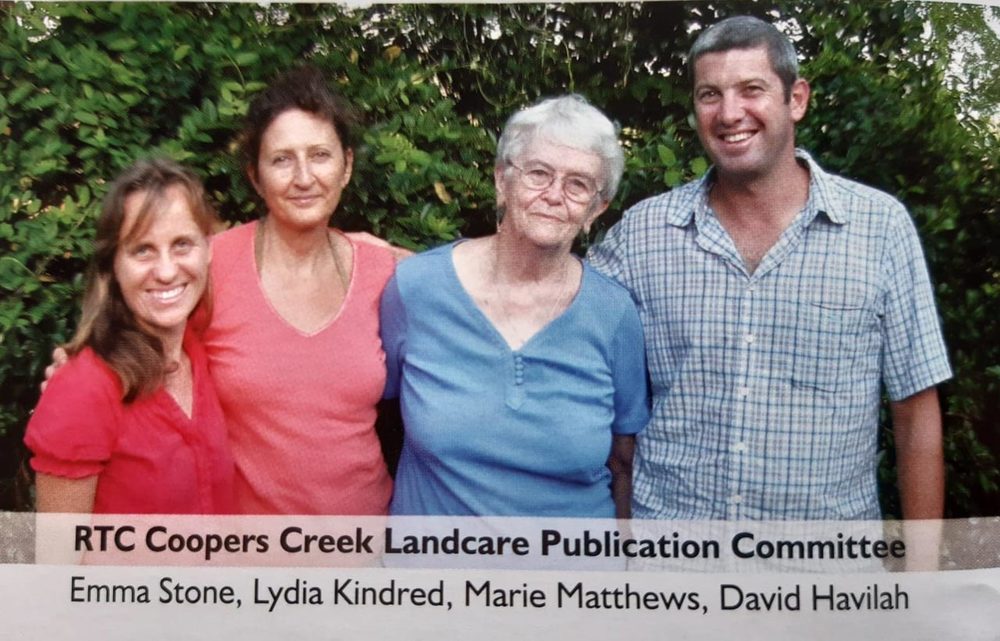

Lismore's Emma Stone was one of the co-authors of Coopers Creek: A Place of Stories.

Lismore's Emma Stone was one of the co-authors of Coopers Creek: A Place of Stories.“Water was shared by the animals. Water was shared by everyone. Water didn’t belong to anyone. Everyone was responsible for that water. There was, and there still is, a spirit of the waterhole. Be mindful. No-one can live without water.”

R.C. Gordon, Widjabul descendant, in Coopers Creek: A Place of Many Stories.

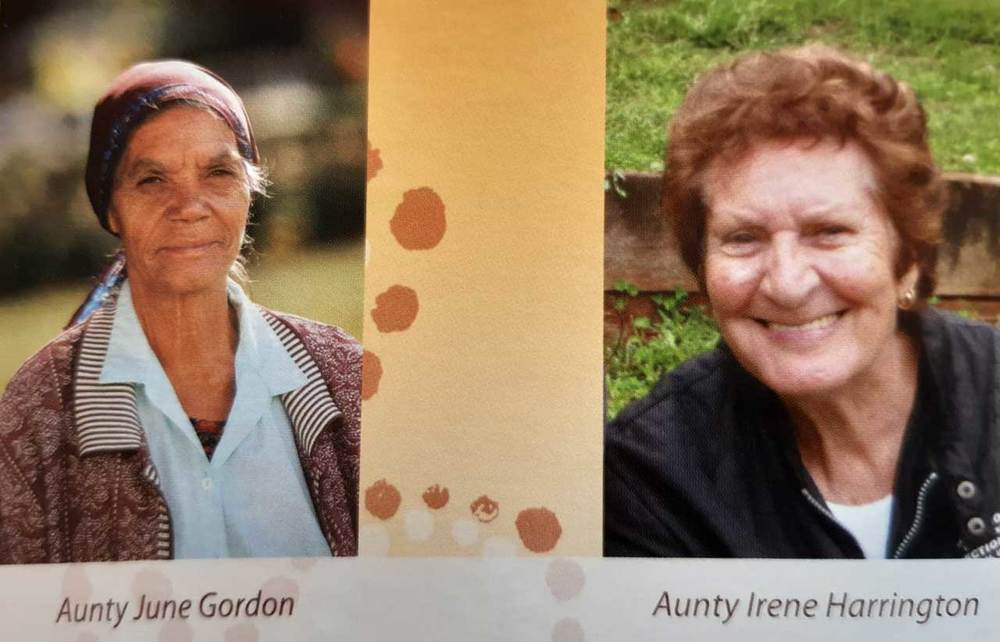

Widjabul Elder Aunty June Gordon remembers collecting fruit and vegetables that washed down the river from the farms above the community she lived on at Cubawee when the 1954 flood swept through Lismore and surrounding areas. She also remembers dancing at a corroboree the year before at the Lismore Showground.

The area is the site of an old bora ring and sacred to the local Widjabul/Wy-abal people and Aunty June believes the flood came as a direct result of that corroboree. During the flood, as Lismore went under water and cattle were washed downstream, the Cubawee community moved up the hill to shelter at the nearby Italian farmers’ banana farm.

Aunty June told these stories to historians Emma Stone and Marie Matthews while sitting by the river near Ballina Road bridge in Lismore.

Coopers Creek: A Place of Many Stories

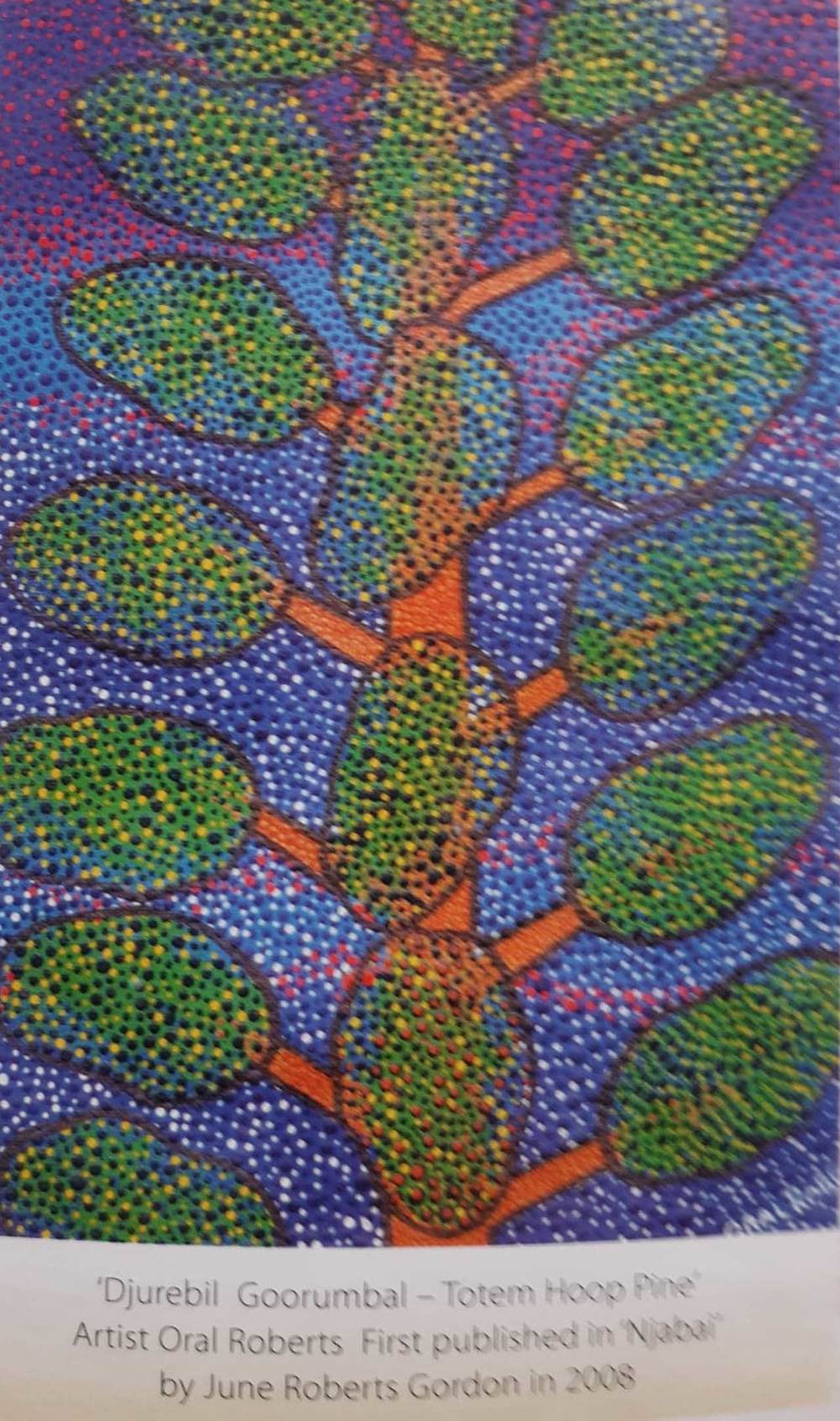

Aunty June’s stories, along with other stories from other local Indigenous Elders, were to become part of the book Coopers Creek: A Place of Many Stories. The book was part of the Reconnecting to Country project and is a collaboration between the Widjabul tribe of the Bundjalung nation, Rous Water and Sustainable Futures Australia.

Marie and Emma are part of the book’s publication team who spent three years consulting with local Elders and gathering information about the history of the local area surrounding Coopers Creek, a tributary of the Wilsons River.

Dunoon dam

Emma said the book played an instrumental part in her recent submission to Rous County Council about the proposed new dam for Dunoon.

“I quoted some of the book as I talked about the significance of the waterways to our area,” she said.”

Oral histories

As Emma and Marie gathered oral histories and searched through dusty local archives, reports, newspapers and historical texts, they uncovered hidden stories and discovered the history behind local people’s connection to country. Their goal was to re-tell history from the perspective of the local Indigenous community, as well as the white settlers’.

By embracing Widjabul stories and the significance of land to Indigenous people, they wanted to create a new picture of local history with hopes for a better future for land and water management.

Widjabul stories

“History is usually told from a white perspective and it’s important we see the story of this place from an Aboriginal and white point of view,” Marie said. “It’s possible the book could change people’s thinking to be more inclusive, instead of just seeing things from a white Western perspective. It’s about the idea of caring for land as much as trying to get something out of it.

“Rather than us looking at our own private land property boundaries, we need to have a sense of how this area fits into the water catchment. Water is the life-blood of the land and we need to look at the whole landscape more. Upstream is just as important and everyone has a responsibility for the creek.”

Emma and Marie have been involved in local Landcare restoration projects on the Wilsons River and Upper Coopers Creek including ongoing projects at Rosebank Reserve.

Local mystery

While they were compiling information for the book they found a reference to a local mystery mentioned in a Village Journal from August 2006.

Local bush regenerator Garth Kindred had uncovered a series of three stone walls on a steep slope at Chendana, Rosebank. No-one knew why they had been constructed but one idea was that during WWII the women around Federal made a wall to keep their minds off their men still at war.

It was also thought that it could have constructed to keep livestock in, or maybe made by the efforts of people clearing their land selections after WWII. The mystery still remains.

Art of research

For Marie and Emma, learning the art of historical research to put together a book required dedication, persistence and an open mind.

“I loved doing research but I didn’t have a clue how to start,” Marie laughed. “I knew Corndale School had archives and I spent days going through their records. It was hard work: there was so much information and you don’t know what you’ll come up with. I photocopied anything about Coopers Creek and pooled information from Village Journals, books and newspapers. I noticed there were gaps in available information: there was very little about the wars, only a little information about raising money.”

Cultural protocols

As well as working with the Coopers Creek catchment water-users group, consisting of farmers, government and local representatives, Marie and Emma spent many months learning the right cultural protocols so they could work with the appropriate Elders and knowledge holders in the Indigenous community.

“It was challenging, but so rewarding and inspiring,” Emma said. “It took a long time to get off the ground so we could create a bridge between cultures and collaborate with Aunty June, Aunty Irene and Roy Gordon.

“The whole process has helped with communicating with all people on the land now about how to manage the water catchment sustainably.

Different lives, common ground

“We all have different lives but common ground: the dairy farmers and macadamia farmers blame each other for the silting of the creek. Bush regenerators blame cows and point the finger at farmers.

“Our consultative process helped people to relate better to each other and realise it’s not about taking sides but working together to restore the creek banks and river systems.”

Two cultures

The book is filled with stories highlighting the differences in how the two cultures, Indigenous and white, lived on and managed the land very differently.

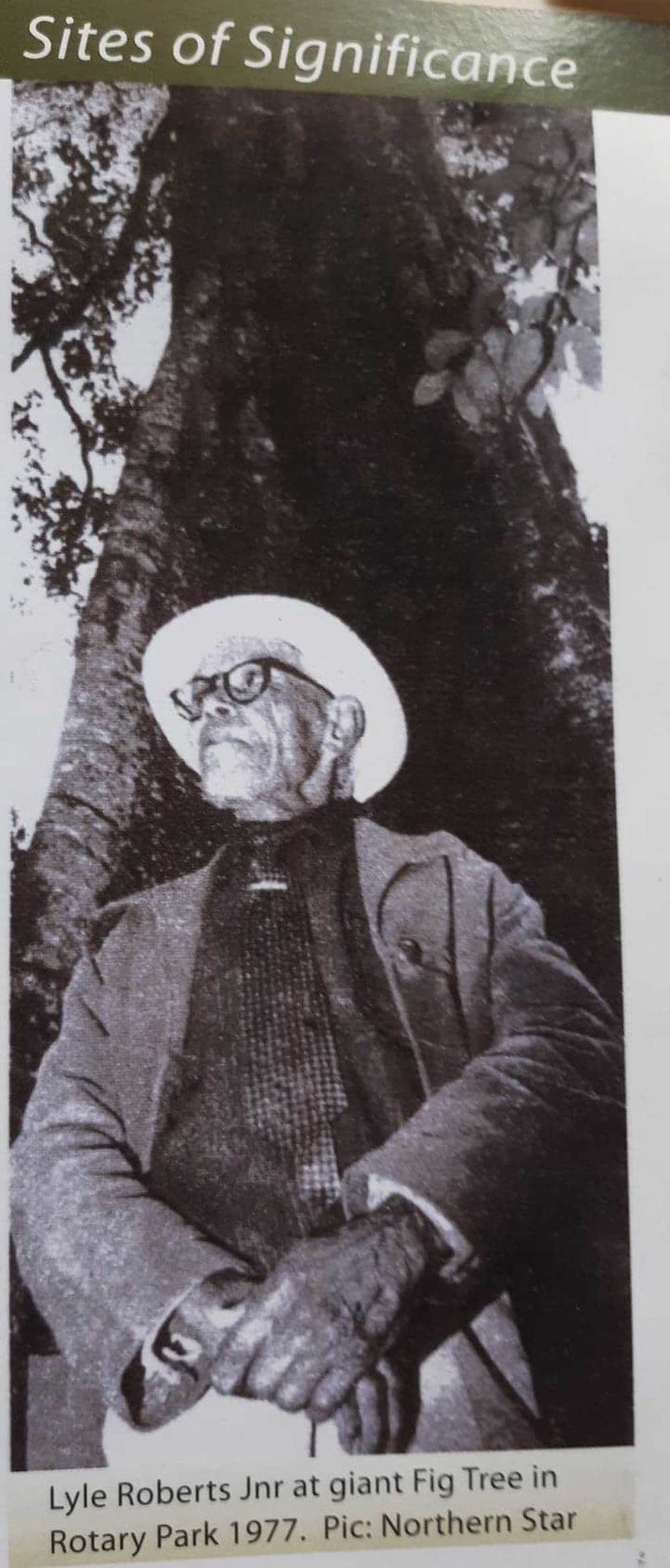

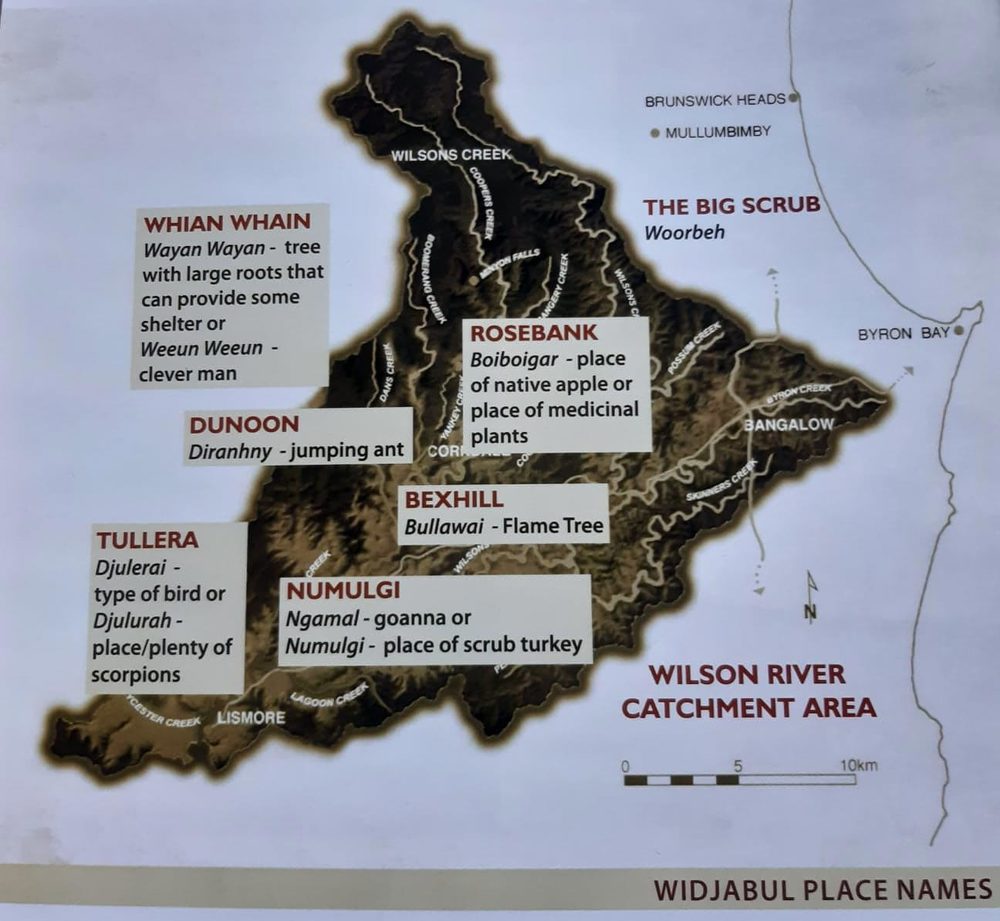

While the white settlers portioned off and ‘owned’ the land they found here, the Indigenous tribes have long been its caretakers. Each clan of the Bundjalung Nation is responsible for particular areas of country and there are 111 dreaming or ‘creation’ sites recorded in the Northern Rivers region, many of which are linked by traditional pathways or travel routes.

Bad spirits

In the book, there are stories of people swimming at the Coopers Creek causeway, and Aunty June tells a story about not being able to swim in certain waterholes because of the bad spirits that lived there, as told in local Aboriginal legend.

She also recounts a Widjabul water creation story with the moral that everyone should protect the water and keep it clean.

Swimming

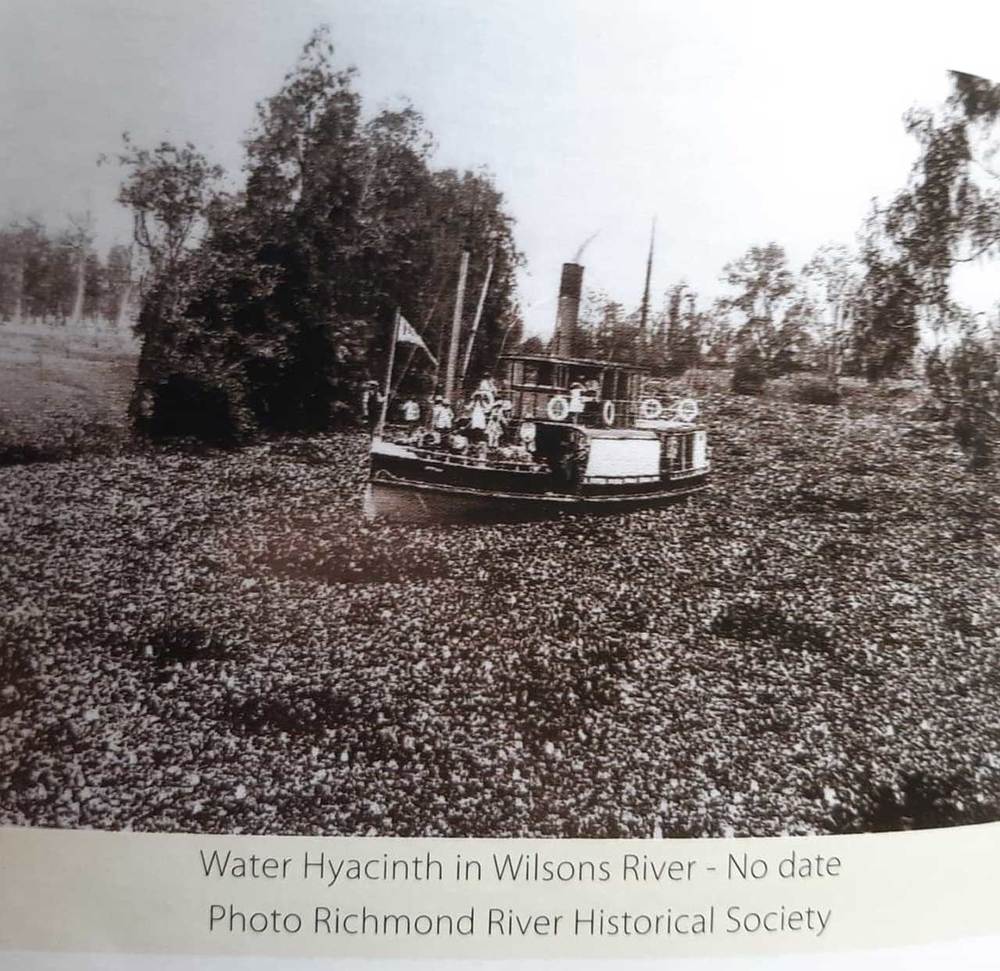

Wilsons River and Coopers Creek were once popular places for swimming for both Aboriginal people and white settlers with catfish and perch up to 28 kilos in weight being found in the river. Due to the poor management practices of white settlers the water became more polluted and fishing became less viable due to habitat degradation and over-harvesting.

It is known that the eastern freshwater cod, once found in abundance in the Richmond River system, began to decline from 1926. While the species is now protected the last authenticated capture of a wild cod was in 1971.

A number of floodplain restoration projects have been taking place in the local area, including at Boatharbour and Corndale, and there are signs that water quality is improving.

Tale of three brothers

From an Indigenous perspective, the story of the peopling of Wiy-abal country began with the tale of how three brothers left their grandmother behind when they were collecting food at Evans Head.

She became so angry that she climbed onto Goanna Headland and made the waves sink their canoes and the brothers came ashore in Ballina. Each brother went on to populate the land in different areas: one went north to Tweed, one came up the Richmond River and one went south to the Clarence River area.

White perspective

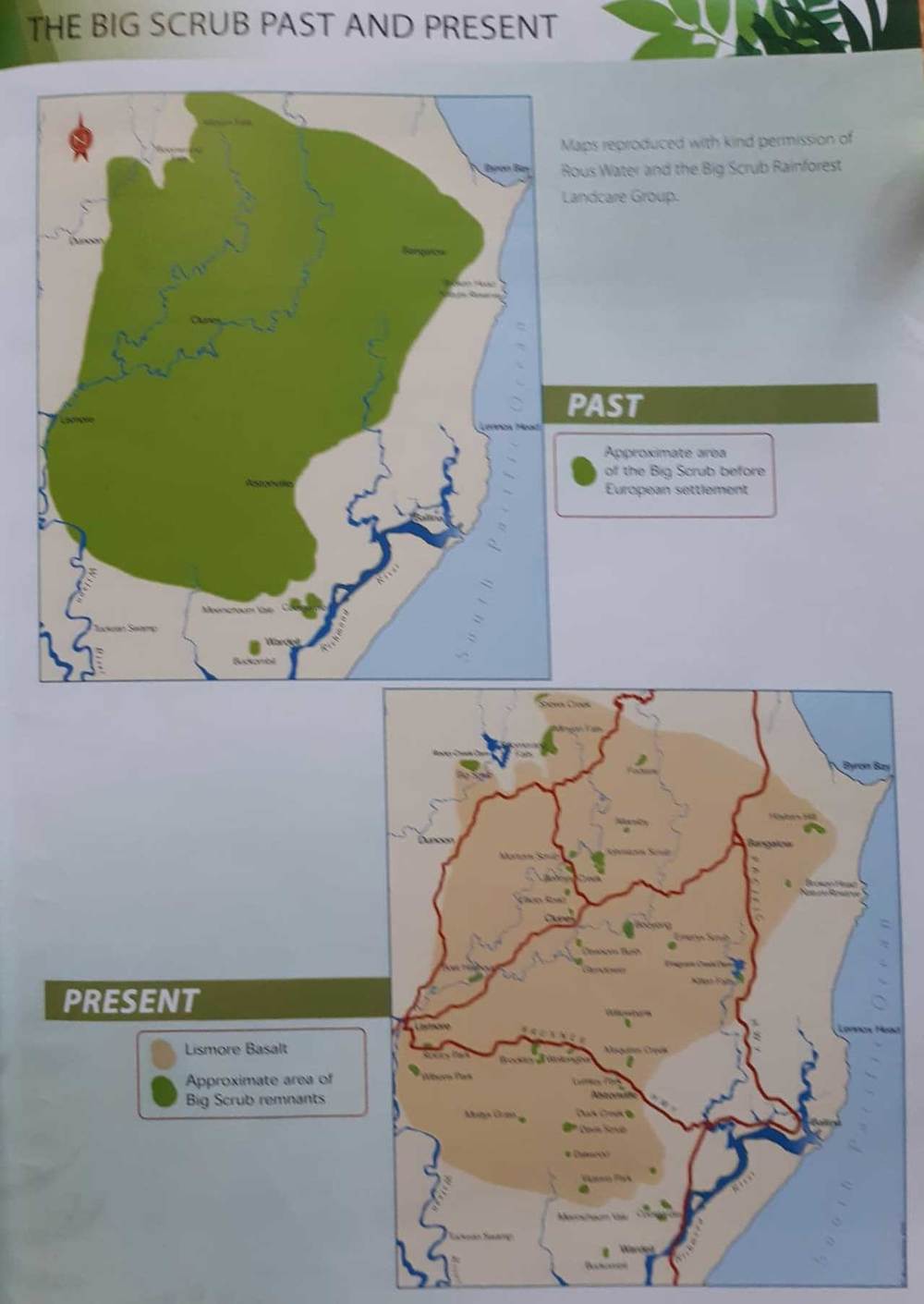

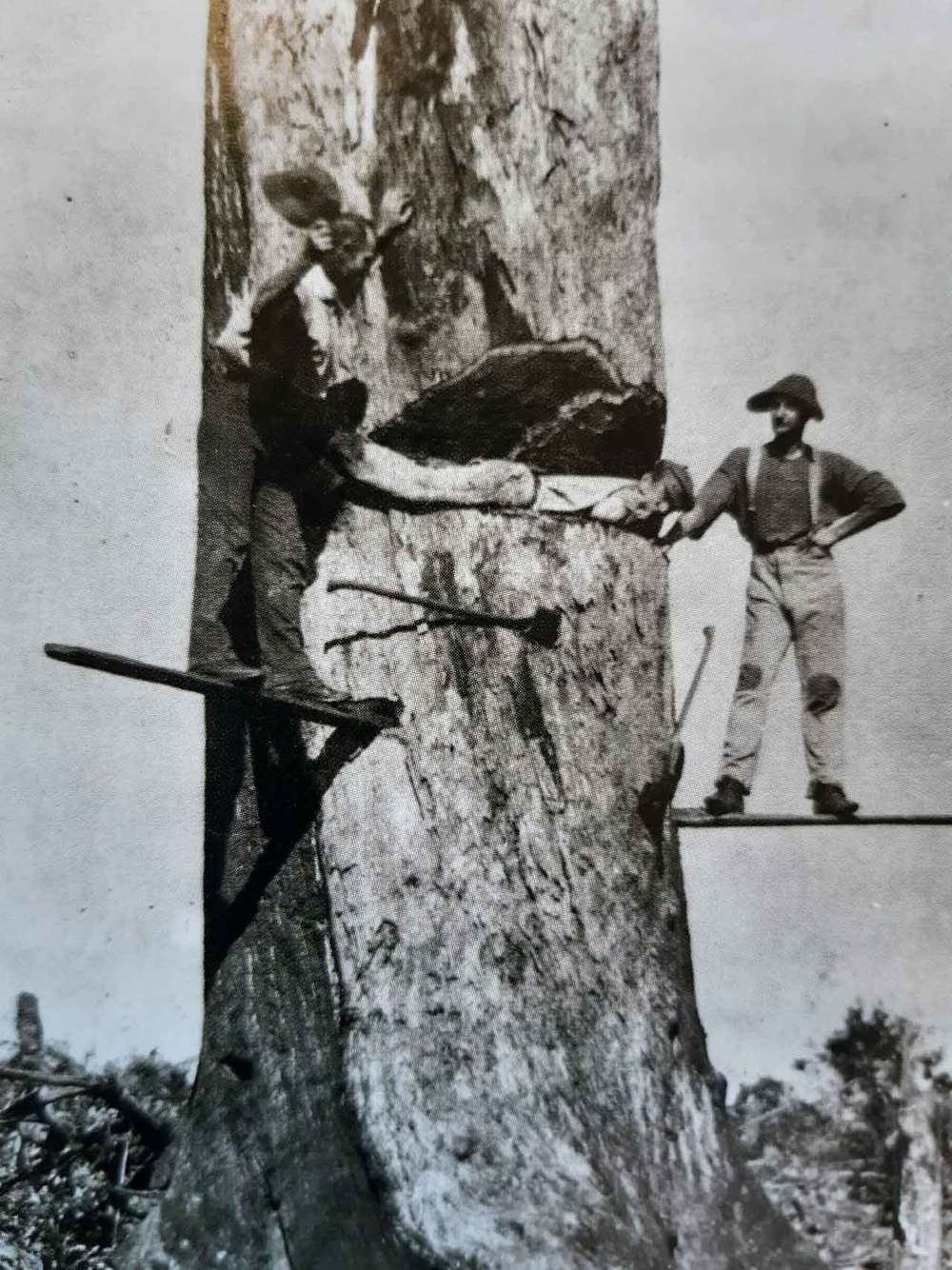

From a white perspective, it was in 1828, when Captain Henry Rous discovered and named the Richmond River that the occupation of the area by the new white settlers began. In 1842, the first cedar getters and their families sailed up the river to access the region’s ‘red gold’, the cedar which was to be steadily cut out from the Big Scrub, subtropical rainforest which covered the region.

Cedar camps

Cedar camps were set up on the banks of the river and one such camp that accessed Coopers Creek was found at Bald Hill (later renamed Bexhill). It thought that Coopers Creek was named after George Cooper, one of the first cedar cutters.

More farmers moved into the area after the John Robertson Land Act of 1861 opened up the Big Scrub land for farming. The dense jungle was cleared and burned and the first crop to be planted was corn, giving birth to the village of Corndale.

Cattle

Once the new settlers introduced an exotic strain of paspalum grass to the area the dairy industry was able to flourish as food for cattle became more abundant.

“With white settlement the Indigenous people became trespassers on their own land,” Marie said. “Life was difficult for the farmers with their English farming practices and animals but the Aboriginal lifestyle was much more comfortable, living on the land.

“The Aborigines often worked with the cedar getters to clear the land and the young Aborigines were often found to be better rafter drivers and bullock drivers than the sawyers themselves.”

New settlers

Life was not easy for the new settlers. The roads were basic and everything was carried by horse or on foot. When wheeled vehicles began to be used more bridges became necessary to help people get over the fast- flowing creeks.

Bridges

Putting in bridges was quite expensive however and the job would go out to tender. In 1888, Coopers Creek bridge eventually opened near Corndale Hall, making life easier for farmers trying to transport their crops and dairy cream.

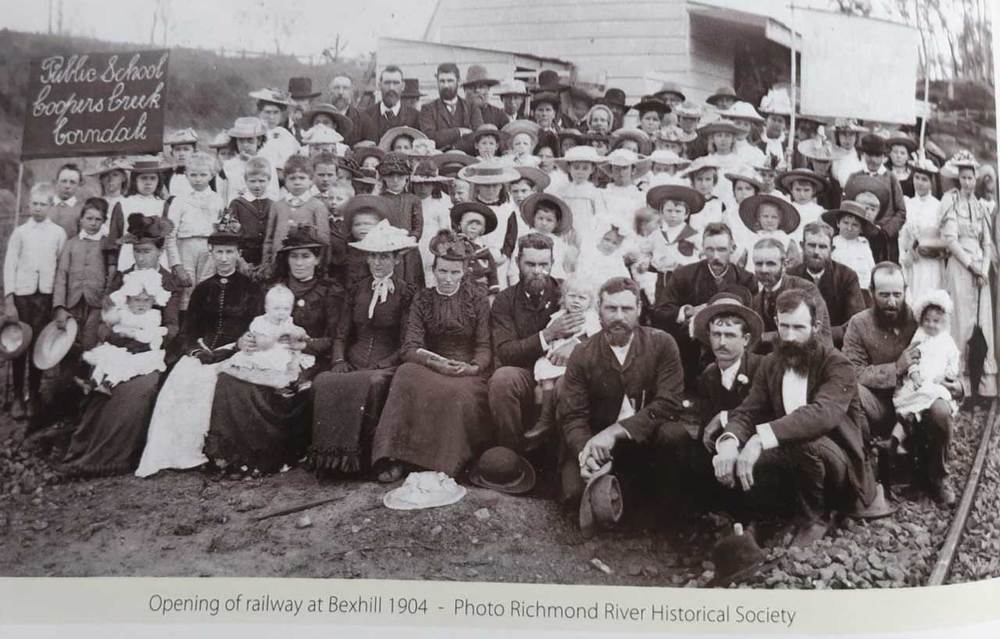

Railway at Bexhill

It wasn’t until 1904 that the Lismore-Tweed railway line opened and the first passenger train stopped at Bexhill. Dairy farmers would take their cream to Bexhill railway station and then on to Byron Bay. In 1913, a butter factory opened at Corndale.

“I liked discovering stories of co-operation between the two cultures,” Emma said. “The women and children helped to bridge the divide and learned each other’s languages. The Indigenous women’s midwifery skills were also highly valued.

“It wasn’t until the 1960s that white people began to see Aboriginal people as real people, not as lesser beings and part of the country’s flora and fauna. I often felt uncomfortable when reading some of these histories: I felt a strong sense of shame for the inappropriate conduct of the settlers.”

Healing wounds

“This is a positive journey to heal the environmental and social wounds and it’s an opportunity to understand the past,” Marie added. “The current generation of Elders have a limited knowledge and as they pass on history we need to keep the stories alive, because they can disappear so quickly.”

Secrets

While some of the land we walk on still remains secret, gathering these stories from two cultures will help to keep the past knowledge alive and as caretakers of land, we can hopefully move into the future, having learned from our mistakes and successes.

Coopers Creek: A Place of Many Stories is a great resource for research in the home or office and Dunoon Primary School have used it in their Aboriginal Studies classes. The book also holds some amazing photographs of what life was like over 100 years ago, including some of Aboriginal and settler families during the late 1800s.

The development of the book was funded by a grant from the Environmental Trust.

Buy the book

If you would like to buy a copy of the book, you can find it at the Dunoon General Store and the Dunoon Post Office, or contact Emma Stone by email landcare.support@brrvln.org.au