Lismore Hospital surgeon travels to Gaza to help the wounded

Simon Mumford

11 June 2024, 9:02 PM

Dr Herwig Drobetz in his office at Lismore Base Hospital

Dr Herwig Drobetz in his office at Lismore Base HospitalWe have all read about and seen horrific images and visions of the Israeli-Gaza war. One local doctor has seen the devastation first-hand, spending six weeks in an ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) hospital in the humanitarian zone to give support to the local healthcare and humanitarian workers who have been helping injured people from both sides of the war without reprieve since 7 October 2023.

Dr Herwig Drobetz is an Orthopaedic Surgeon at Lismore Base Hospital. He has been involved in humanitarian work since 2018. He has travelled to Syria with Doctors Without Borders, Yemen and now, three times to Gaza. He usually goes to protracted European war zones, which means the war has been running for a long time or is in a cease-fire.

This was his first time with the Red Cross.

"I have a contract with the hospital that I can go away once a year for three months. I take unpaid time off between two and three months, Dr Drobetz told the Lismore App.

"I chose the Red Cross because I wanted to go to Gaza and the Red Cross was the only one who was sending surgeons into Gaza now. Mèdecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) was also going to Gaza, but they didn't send any surgeons. So, it was a win-win situation for this deployment because it's an active war zone."

Dr Drobetz explained the deployment was for a maximum of six weeks, which includes travel that takes approximately a week to get to Rafa and another week back.

The journey to Gaza is via Egypt, where briefings are held before the final two-day trip to Gaza. It is the same journey on the way home.

The European Gaza Hospital was filled with doctors and nurses who treated a thousand patients daily in Rafah.

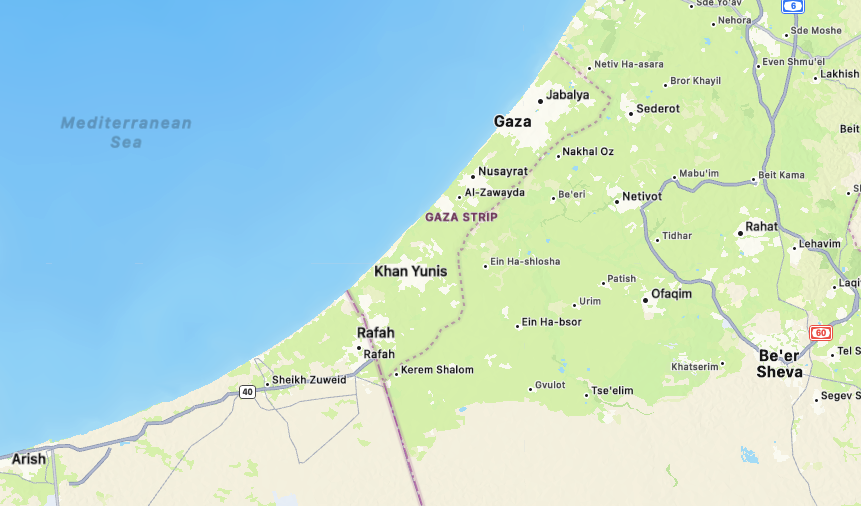

"We were in the European Gaza Hospital, which is in South East Gaza on the border between Rafa and Khan Younis, and then I was also working at the ICRC Field Hospital, which was completely newly built. I arrived on the day when it was opened, that was on the eighth or ninth of May. That's in the southwest of Gaza, and that's in the humanitarian zone, also in Rafah, so it's on the beach."

In previous humanitarian visits to Gaza, Dr Drobetz experienced different environments. The first time, there was targeted bombing for three days hitting specific buildings, and the second time, in 2022, it was not an active war zone. Everyone could move about freely, and cafès, restaurants and shops were open for business, so the trip offered some downtime to enjoy the people and the culture of Gaza.

"Gaza is beautiful. There was an old town, there was a life, even though life is always hard in Gaza," Dr Drobetz said about his 2022 trip, "But in 2022, you had this optimism, and people were opening world-class cafès and restaurants. That's obviously all gone now."

"There are 1.5 million people living in an area the size of Lismore city in tents. There are 20,000 people living on the hospital grounds. Imagine 20,000 people living in the Lismore hospital. They were living in hallways, scanner rooms, the nursing station, there are tents and makeshift buildings everywhere."

Dr Drobetz describes his daily life.

"Well, you see war wounded. There are patients who get either shot with handguns or machine guns or they have injuries from explosives, like grenades, or a mine. There are patients whose house gets bombed, and they are buried under the rubble for up to 12 to 24 hours. They have severe soft tissue injuries, all sorts of breaks and chest injuries."

"You see burns, lots of burns, because many of the Palestinians in Gaza now live in camps for internally displaced people, so they live in tents. Often, there are 5, 7 or 9 people in a small tent. They cook on the floor, there's little children, they throw over the stove, and they have severe water or soup food burns or chemical burns."

"We specifically treated war-wounded patients because that's the biggest need. So, currently, there's an estimated 70,000 people injured. That takes decades to work that all up."

"At the European Gaza Hospital, we had about 1000 patients per day coming to the emergency department. By comparison, Lismore is about 130 to 160 per day. We had 1000 patients coming in, and there were about six or seven doctors."

"I was not working in the emergency department. But, from this 1000 patients, at least 40 are severely injured, statistically, and another 50 are a bit less injured. The majority comes in for relatively small stuff. There are a lot of people who have diabetes, but the health system in Gaza has collapsed. Only 10 out of 36 hospitals in Gaza function. So, they can't get diabetes medication, that's why they go to ED, because it's the only way to get access to regular medications.

"So, you have this massive mixture of patients, but about 30 or 40 were severely injured."

Not all patients were treated by the Red Cross. Dr Drobetz explained there were other organisations from America and Jordan that treated patients alongside the dedicated local staff.

"There were a lot of surgeons. That hospital is a really big hospital; they have like six or seven theatres. It was the largest, still functioning hospital in Gaza. The Red Cross was working in one of the theatres there, and we also managed a ward where we had 50 beds for patients. We treated whatever came our way. So, we had between four and nine operations every day. Sometimes, you would have four big ones; then it's a long day. If you have nine small ones, it's not such a long day. The numbers don't really indicate much; it depends on how involved the operations are.

"We worked six days a week. On Fridays, that's like the Sunday here, we tried to have a rest day, but if something comes in, there is no rest."

Living conditions were very basic during Dr Drobetz's deployment.

"You need to imagine that we were sleeping in five rooms in what used to be a nursing school where there'd be eight people sleeping in a room. I was basically sleeping in the kitchen. It's always loud. Somebody's always coughing, somebody always has a chest infection, everybody gets a chest infection, somebody has gastroenteritis, so they get diarrhoea, you get vomiting because the water is not clean. There's huge noise with people, you have no privacy. There's two toilets and sixteen people trying to make breakfast in a really small kitchen."

"That's all okay, you get used to everything. No hot shower for six weeks, not a problem at all. But then all night there are drones flying, there's fighter jets flying, there's bombings very close to the house, there's gunfights close to the house, there's tanks shooting, there's the Navy shooting from the sea over the hospital into Rafa. So, it's mayhem. And you don't notice this because you get used to everything. You do your yoga in the morning on the rooftop, and the Navy's shooting over the hospital, it doesn't become normal, but you get used to it."

"But what you don't notice is, because you are constantly in tension, you're constantly working, the stress. You are always in a state of exception and you can't sleep well, even though you don't notice it. So, it's very exhausting. That was the spatial thing as well. Normally I'm not that exhausted when I come back because you go for two months and I can go out and drink coffee and have a restaurant and have nice talks and there's no active hostilities around me. So, the work is only just one part of the whole thing. That work is my comfort zone because that's what I'm used to. That's not the difficult part for me personally. That's what I learned anyway. It's everything else around it. I'm used to it to some extent, but this was very tense."

"We were advised not to leave the accommodation. We left in the morning to go to the hospital, that was about 100 meters away, and then in the evening, we went back, and then you don't leave. There is nothing else to do, so you might as well work. It's very simple because life reduces itself to sleeping, eating and working. There's not much else you do. If you have time, on the Friday, you watch a movie, you talk, you play a game, or you do some exercise. I tried do some exercise every day."

"You don't have all these daily life things you usually need to do, like I don't need to go shopping, I don't need to take my car for a service, or I don't have to pick up anyone. All these things are gone. So, your day is actually quite long."

Dr Drobetz praises the skills and courage of the local medical staff who live in those conditions every day that this war goes on.

"I have had the privilege and the honour and the luck to work with some of the best surgeons I've ever met, who are Palestinians, who are local plastic surgeons or local orthopedic surgeons. If they would be anywhere else, they would be world famous. They are amazing. What they can do with very little equipment and very complex injuries because Gaza has very specific complex injuries, and they have thousands of people who get shot in the legs, young men mostly, who have severe fractures and soft tissue problems in the lower legs. They reconstruct them, which is extremely involved and difficult, and there's not many people who can do that. The work they were and are still doing is amazing."

(Dr Drobetz with Hassan, a translator)

"So, I learned much more there than I could teach them, even though that's an interest of mine, this kind of surgery. I consider these people very close friends, so that's why I wanted to go back now because it's important to show them that you don't forget about them and even the fact that you go there already helps. Some of them I've managed to see again, and some of them I couldn't see again. Gaza is only 40 kilometres long, but my very best friend was maybe 20 kilometres away, but it was impossible to go there because there was a frontline with access impeded. It was, unfortunately, impossible. I tried to send him cigarettes and chocolate because they are the most coveted commodities at the moment. A packet of cigarettes was 250 US dollars when I was there."

(A Google map showing the 40km long Gaza strip)

"You meet lots of dedicated people. The theatre nurses came to work every day, even though they hadn't been paid since October. They were all employed by the Ministry of Health. It's sometimes life-threatening for them to go to work because they have to cross the front line. One of them had his house bombed and lost father, mother, brother, sister, eleven relatives, yet he still came back to work two days later. You cannot imagine losing everything and then still coming to work and still having empathy and still cooking for us, even though they have hardly any food. That's an impressive act of resilience and also heartbreaking."

War zones have a massive effect on the people that we see on TV or the internet, but they also have a large impact on the medical staff that go to help.

"Of course, it affects you because there's a lot of different movies in your head afterwards.

"It was absolutely heartbreaking to see the pain and the suffering and sadness every day when we walked from the nursing school to the hospital. And for the people, it was extremely important that we were there because as long as there are NGOs, so non-governmental organisations or humanitarian organisations, then they feel there is much less chance that the hospital will be impacted by hostilities.

"The people were panicking because the Israeli Defence Force gave evacuation orders for Rafa, and that was very close to the hospital. We were still in a humanitarian zone, but it was close to the hospital. People were very nervous. It was important that we were there. Just the simple fact that we were there gives them some sort of security."

"We got stuck for 10 days because the borders were closed, so we couldn't get out. We had to wait for 10 days after our date, and we were supposed to go, and then it was not really clear when we would get out and how we would get out because the border into Egypt was closed, and there was no indication when it was opening again. So, we had to go out via another border into Israel, and it was all very difficult."

"Of course, you're relieved to get out because the war was getting closer and closer. But you are also really sad because you have survivor's guilt or you leave people behind you are really close to. It is all the same. Every mission is the same. I was in Yemen, I was in Syria and Gaza, and every time, it's the same: you're happy to go home, and you are sad that you go home."

"Of course, it takes time to settle because you have all the movies in your head, you can't sleep well from jetlag, you think about it a lot, so it takes a while to settle, and that's okay. That's the price you pay for doing these things, you know, whether you call it PTSD or whether I call it working through it, in six to eight weeks, it settles down until it becomes a memory. You also experience really nice things there, like we were sitting with the nurses and talking and even joking and they cook for us and it's very bonding and if you give out cigarettes to the drivers and then you have a cigarette and the tea together that's really nice."

"These people are all highly intelligent people, the drivers have been engineers, and many of them have a university background. They're really interesting people to talk to. Their English is really good. I was together with a Serbian and Dutch surgeon who were really nice, and I was also with the principal nurse from Brisbane who travelled with me. We were in Egypt together, and we were in the hospital together, and she became a really good friend. It also has really good things and then it settles down after eight weeks. Then your life here becomes a routine again."

(Brisbane nurse Ruth Jebb travelled with Dr Drobetz to Gaza)

"What I want to take away from it is that I don't want to get upset about little things ever again in my life after seeing what these people can tolerate and how hard their life is, and they can still show empathy.

Dr Drobetz wants to praise his orthopaedic team at Lismore Base Hospital for picking up the workload when he is deployed each year for two to three months.

"I'm always looking forward to going back to work. I love Lismore Base Hospital. I think it's the best hospital in the world, and I work here with the best colleagues, the best nurses; everybody is so nice, and everybody's so supportive.

"Because I'm an orthopaedic surgeon, I usually need to plan it. I can't go on short notice because it is very unfair towards my team to leave them on short notice. So I always need to plan. I tell MSF, I tell the Red Cross that I can go next year in April and then they will try to find something for me for April. Then I tell my team who are awesome. The Lismore orthopaedic department is amazing, they compensate for me being away. They have to work more, and they always make it possible that I can do these things. So, I'm super, super grateful that we have such a great team."

"It's usually difficult for me to go on short notice. This was a bit different because I said I would like to go to Gaza, and they asked me five weeks before I left, and my team was so nice to make it happen. But usually, that's difficult."

For anyone thinking of going to Gaza to offer their help, Dr Drobetz has some advice.

"I think it's hugely important that you only do this with a big organisation like the Red Cross or Doctors Without Borders. It has to be a big organisation because they have teams who are dedicated to the management of safety and security of the staff.

"If you can't go, then you can always donate. That's the second best thing you can do to help. Reputable organisations like the Red Cross or MSF, they can use that money. It doesn't matter who's right or wrong in this war. The work of humanitarian organisations is based on reducing the human toll of armed conflict on all people impacted by the violence. The Red Cross, MSF, they treat anyone. Anyone who comes in gets treated, it doesn't matter whether they are Palestinians or Israelis. The hostages get treated by anyone. It doesn't matter. It's never a solution; the purpose of humanitarian medical assistance is not about providing a resolution to any conflict. It is just help. Essential help. That's what this is about."

You can donate to the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) by clicking here.