50% new car sales electric by 2035: is it possible?

Simon Mumford

20 September 2025, 8:02 PM

Last Thursday, the Federal Government announced its ambitious 2035 climate change target range of 62% to 70%, which was recommended by the Climate Change Authority (CCA).

The Federal Government said, "It is an ambitious but achievable target - sending the right investment signal, responding to the science and delivered with a practical plan. It builds on what we know are the lowest-cost actions we can deliver over the next decade while leaving room for new technologies to take things up a gear."

It also said that, according to the best available analysis, the majority of the reductions for Australia to reach the initial stages of our 2035 climate change target range can be achieved through actions in five priority areas, building on its existing policies. These are:

- Clean electricity across the economy: more renewable electricity generation, supported by new transmission and storage (including household batteries)

- Lowering emissions by electrification and efficiency: our New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, supporting consumers switch to EVs and improving energy efficiency

- Expanding clean fuel use: establishing a low-carbon liquid fuels industry and supporting green hydrogen

- Accelerating new technologies: through Future Made in Australia investments, and innovation support through ARENA

- Net carbon removals scaled up: enabling landholders to earn money for eligible carbon storage and a robust ACCU scheme

In points two above, the CCA has said that, at some point before 2035, half of the light vehicles sold should be electric vehicles (EVs). The Lismore App asked the question, Is that achievable? After all, Australia is larger than all of Europe; we have a very large country and a love of caravanning.

To give you an insight into the gains that need to be made, the Australian Automobile Association shows that so far in 2025, 72.19% of all new light vehicles sold are ICE or driven by internal combustion engines only. 7.87% are BEV (battery electric vehicles), 4.28% are PHEV (plug-in hybrid electric vehicle), 15.66% are hybrids, and 0% are hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles).

The biggest selling BEV are medium-size SUVs at 4.18%, which account for 24.91% of all new light vehicles sold this year. The largest selling car in Australia in 2025 is the Toyota Rav4, a car that is only available in hybrid, PHEV and petrol versions. Does that show Australia's concern for purchasing BEVs? With range anxiety and charging options a real concern.

The next best-selling cars are the Ford Ranger and the Toyota Hilux.

According to Tom Rocks from Lismore Toyota, the problem we face is that Australians need and love vehicles that carry a load, something that current BEVs cannot achieve. That could be for work purposes, such as a tradie or a farmer, or it could be the tens of thousands who want to tow a caravan and see Australia.

"I think the answer is that pure battery electric will maintain a particular part of the market. But will it be 50%? I don't know. It will definitely be a certain percentage of the market. But what percentage by 2035, who knows?

"The material science is changing so quickly, you've got zero emission biofuels, you've got hydrogen, you've got fuel and power sources that have a zero carbon footprint, that allow you to have a ladder chassis combination vehicle that can tow, and can weight-load and can go four wheel driving.

"As an example, the material science at the moment only allows for pure battery vehicles to be aluminium monocoque structures that have an 800-kilogram lithium-ion battery pack at the bottom of the car. And so therefore, even if their charge times increase, they're not going to be suitable for a lot of roads in most countries, including Australia."

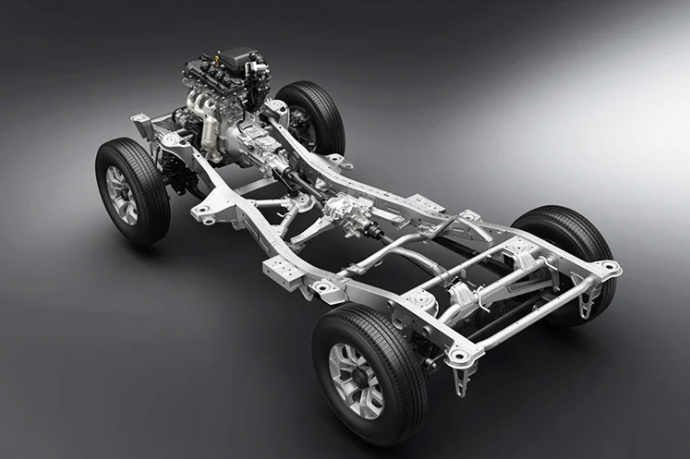

Currently, your Toyota Hiluxes, Range Rovers, and Land Cruisers have a type of chassis known as a ladder chassis. The engine, drivetrain, and suspension are bolted onto the ladder chassis, offering flexibility for different builds (single cab versus dual cab) and offering the high ground clearance and extensive wheel articulation needed for rough terrain. This allows larger cars to weight-load and/or tow.

(An example of a ladder chassis)

Lithium-ion battery packs that are used in BEVs cannot be weight-loaded.

"You've got an 800-kilo battery pack at the bottom of the car. If you put two batteries in the car, it turns into 1,600 kilos and but you don't get double the range. You only get a 25% increase because you've added so much weight to the car. Will we get to 2035, and it will be all electric? No, it won't be. But will we be carbon neutral in our automotive industry by that point? Probably, but it's by other means," Tom said.

So, the difference in the way the cars are built is a significant challenge. However, there are alternative solutions to achieve zero emissions other than all-electric that will help achieve the Federal Government's climate change targets.

Tom said that Australia's mining companies are using synthetic diesel fuels as a way to transition to zero emissions by 2050 because the technology does not exist for them to use 100-ton trucks using batteries.

On its website, Mining Technology said, "BHP has teamed up with BP to trial the use of a blended HVO (hydrotreated vegetable oil) diesel at its Yandi iron ore mine in Western Australia’s Pilbara region. The trial “provided valuable insight and knowledge in renewable diesel”, with BHP saying that the results will be used to determine how renewable diesel may be “a practical complementary transition pathway” to its operational decarbonisation plan.

"Mining giant Rio Tinto has already made the shift to biofuels. In May 2023, its Boron operation in California became the world’s first open-cut mine to fully transition all its heavy vehicle fleet to renewable diesel, reducing emissions by up to 45,000 tonnes per annum (tpa) of CO₂ equivalent."

Tom said that a major benefit of synthetic fuel mixes is that they can be used retrospectively.

"You can put it in older cars, so all of a sudden you don't have to scrap every car in the country, you can just use a biofuel of some description that lowers the CO₂, but you still get the same output. So you can say, caravan. You can put all your tools in the back. You can have all of that trade, utility, work and still have that CO₂ output."

There is so much on the runway that will drop in the next sort of four or five years. As an example, once they produce solid state batteries, which are very different to a lithium-ion battery, you're going to have way shorter charging times, and you're going to have way longer range, but you're going to also have a slightly lighter car. That solid state battery will be paired with a small combustion motor of some description, whether it's a two-litre diesel or a 1.8 litre petrol, and those two components together, you're going to get a couple of 1000 kilometre range, and that's coming from a 50 to 55 litre tank.

"The CO₂ outputs will be within the NVES (National Vehicle Efficiency Standard) range. It aims to reduce emissions from new passenger vehicles by 60% by 2030 (currently 141 grams per kilometre). But you're talking 2000 kilometres or 1800 kilometres, with a 1.8 litre petrol motor, with a solid state battery pack, and it can weight-load. That's probably where it will go.

"The you look at vehicles that are completely battery electric. The battery technology hasn't really developed much. If you look at the range of the Tesla ten years ago, and you look at it now, it is five to seven and a half per cent better over 10 years. They're already at capacity with that type of material science."

Hydrogen-powered vehicles are another technology that is making progress.

"In Japan and America, you can get a hydrogen Toyota. We've had them here in Australia, but unless you're the government or a university, you can't buy them because you can't fuel them. The hydrogen fuel cells take about 45 litres of gas, and they do 600 kilometres, and they emit water, but it's got a really high power output as well. So, once that is mastered, there won't be battery anything. You'll be filling your car up with hydrogen or some type of gas that will give you 2000 plus kilometres, and 300 kilowatts. That will happen in our lifetime.

"There is so much stuff on the runway, and I'm just sort of predicting what I've seen and what I'm told is going to happen, but we'll get there. China's about to release a V12 engine, so this combustion thing's not over.

"Pure electric has a very definite place, and it has one now, and it will continue to have one. But will it be the main power source? I don't believe so, but it has a very definite place across the world."

As the proverb says, "There are many ways to skin a cat".